Marginal gains make more money

Even small adjustments in pricing can boost ticket sales and increase revenues.

Some people will tell you that pricing in the cultural sector should be simple. The problem is that if all your seats are priced the same, then your only option to increase income is either to put the price up or sell more tickets. Failing to introduce an appropriate level of complexity reduces income and leaves empty seats, because it limits the options you have to make marginal gains.

Sir Clive was the originator of the concept of ‘marginal gains’, which has been employed across many different sports. The concept is that lots of small incremental improvements can combine to make one significant overall improvement. By embracing complexity in your pricing, you can achieve your artistic and social objectives, maximising sales – including for difficult repertoire – and promoting accessibility.

This doesn’t mean that prices shouldn’t be presented simply. Your pricing should be ‘swan-like’: serene on the surface, with all the paddling going on underneath to ensure that it maximises the opportunity for income.

Cultural experience

Complexity in cultural pricing is possible because of the subjective nature of customers’ perceptions of the value of a cultural experience. Arts pricing is sometimes compared with airline or hotel room pricing but might be better compared with a meal in a good restaurant. Even if you’re seeing the same production or eating in the same restaurant, the experience is different each time. It changes according to when you are eating or attending, where you sit, the service experienced and who you share the experience with. Both the dining and production experiences also only exist at the moment of consumption, and usually can’t have been experienced beforehand.

When making a booking, a customer is buying the promise of an experience. Not only is there no certainty around the central experience, but most people won’t have attended the venue before. In a theatre context, all they have to inform their decision may be promotional material and the guidance of box office staff or ‘select your own seat’ images on your website. This means the purchase decision is primarily driven by perception, which will be different for each customer each time.

Ultimately a transaction takes place when there is a match between the value sought by a customer (and their ability and willingness to pay for it) and the actual value and price on offer. Crucially, overall value is made up of a huge range of component parts. The opportunity in pricing comes from recognising that different customers value these component parts differently and have a different willingness to pay for them. This means that you can charge different prices and justify the differences in price using different components (e.g. charging different amounts for seats that are more or less valued) or different combinations of components (e.g. charging different amounts for different seats and when purchasing online versus other sales channels). You can them make marginal gains by adjusting the prices of each of the different components, or indeed by adjusting the components, or the combinations of the components.

Sell more, earn more

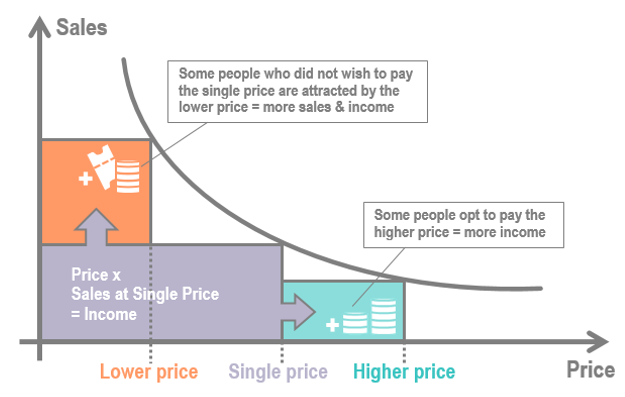

Economic theory (fig. 1) is useful for explaining why it is possible to use lower prices to increase the volume of sales, and how you can maximise income by charging a higher price for some admissions. The key point is that it is inherently beneficial to offer a range of different prices, and you need to be able to justify the differences. This means raising prices for things that some customers are willing to pay more for (justifying a higher price) and reducing prices for things which customers perceive to offer less value (explaining a lower price).

These differences in value are often simple. In a theatre context, it’s primarily ‘what’s the show?’ and ‘where’s the seat?’, with nuance around, for example, performers and style of production. There are also clear differentiators around the timing of the performance, with additional value attached to attending when not time pressured (the weekend) or according to seasonal events such as Valentine’s Day.

Chain reaction

So far, so simple. But, taking a theatre example, even if you only have three different productions, performing on three different days (or times), with three different seating blocks, then you already have 27 different value combinations for which you need to set prices. Then, if you offer three price types – full price, senior and student, for example – that means you’re up to 81 different combinations. On top of that you can enhance the product offer with added value; differentiate prices for multibuys or subscriptions or for members or by sales channel and/or apply transaction or other surcharges. And that’s all before you introduce dynamic pricing! Almost all the same options apply for museums and galleries which charge for admission, with the one exception being seating blocks.

The price is right

Given the number of different value combinations, adopting the approach of ‘same price as last year plus a bit’ soon distorts even the best conceived strategy. Of course, not every value and price combination has to be changed every time you present something new, but even small adjustments can create significant marginal gains which will make it worth the effort for most organisations. How much difference would a 1% increase in ticket income make in your organisation? What about 2%, 5% or more?

Optimising pricing decisions requires a systematic and evidence-based approach. Invest accordingly and ensure the price is right!