Dynamic Pricing: Double the Income, or a Double-Edged Sword?

Baker Richards CEO Robin Cantrill-Fenwick examines the advantages and disadvantages of dynamic pricing, from revenue to regulations.

Ping! My email notification goes off. At some points most weeks a message will arrive from a cultural organisation or visitor attraction saying, “We need dynamic pricing, can you help?” My response sometimes takes them aback. “Yes! But do you really need dynamic pricing, or do you need to make more money?”

Baker Richards has been a proponent of dynamic pricing solutions for nearly two decades, but we take care to ensure it’s the right fit for the organisation we’re working with.

Often, when I get that email – ‘we need dynamic pricing’ – a little digging will discover that yes, the organisation needs to make more money, but the determination to go dynamic is also driven by perceptions. A sense, picked up through networks and marketing, that dynamic pricing is the latest / smartest / most powerful / advanced / timesaving thing and the thing that everyone else is doing. Driven in part by fear of missing out, organisations can reach a point where they instinctively want ‘in’. But it’s important to consider any pricing practice in the round.

Dynamic pricing, most particularly when coupled with high demand, can be a very powerful revenue booster, and in the right circumstances, that’s why we often help organisations to implement it, to great results.

Could something be going wrong with dynamic pricing?

Though dynamic pricing is often presented as new, sophisticated, modern and advanced – and it can be all of those things – it can also be inflationary, unnecessary, expensive, confusing, time-consuming, and annoying.

In late 2022, Baker Richards asked a UK-wide sample of the population what they thought about dynamic pricing. Only around 20% of respondents said it was okay for prices to be raised at busier times. Though when the question was reversed, 60% said it was okay for prices to be lowered at less busy times. So in theory, audiences don’t mind dynamic or fluid pricing – so long as prices are going down rather than up! In reality, dynamic tends not to work that way.

As a practice, dynamic pricing is increasingly catching the attention of consumer rights groups and governments across the Western world. Why? Because it arguably achieves its results at the cost of some transparency, tilting the playing field in favour of the price-setter.

Recently, the Fairer Finance campaign in the UK called on the Competition and Markets Authority to establish clearer rules for dynamic pricing (paid link), including banning the use of ‘from’ prices, and requiring sellers to show the full range of possible prices. This way, buyers can see how much above the base price they are paying, and also have a sense of how the price could change (probably increase) if they wait to buy. Others have suggested that buyers be able to access the history of price changes, or be given a clear indicator of when the price will next change.

These suggestions sound simple enough. But in the real world of ticket commerce, and particularly e-commerce, they can be challenging to implement.

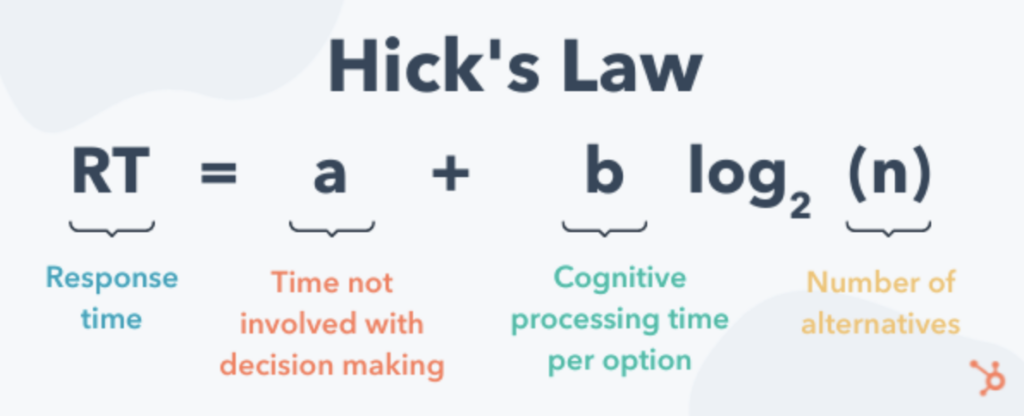

The Hick-Hyman law of behavioural science states that, “The larger the number of choices a person is presented with, the longer the person will take to reach a decision.” So totally transparent dynamic pricing, if implemented as described above, could ultimately hurt purchasing conversion – not just because once they are made aware of the base price buyers may balk at paying over the odds, but because they’re simply overwhelmed with too much information.

Dynamic pricing really works best when it’s simple and fairly opaque – and the signs are that’s a growing problem for some regulators.

Why dynamic pricing works

At its heart, the case for dynamic pricing is simple – with most prices, if you put a few pounds on here or there, or dish out a smattering of 5% increases, most people will still buy, and you’ll take more money. So why not do that? Why charge someone £36 when they’ll pay £39? Given that many cultural organisations sell tickets in the thousands, those incremental £3s soon add up.

Dynamic pricing is also built on an economic truism that dates to Roman times – that everything is worth what someone will pay for it. It’s why, for example, dynamic is particularly well-suited to commercial concerts, popular visitor attractions, and museums and gallery exhibitions which are more likely to rely on maximising the income from a single visit.

But for organisations who aim to keep visitors coming back so they can build a relationship over a long period of time – the case for dynamic can be more double-edged.

All pricing is communication, and what dynamic can communicate is, ‘we price in a way that penalises late booking, or buyers with more popular tastes, or people who can only attend when the schools are shut… But because you’ve been coming for a while you’ll learn over time how to book to get the best value. You’re in the know’. As the basis of a relationship, ‘you will learn how to work around us’ isn’t very inspirational, is it? Particularly when we as consumers don’t always have the choice of avoiding the penalty – none of us live in a wholly rational world where, for example, we always have the option to plan and book far in advance.

Tracking non-buyers as well as buyers

Organisations who want to build a loyal/frequent relationship with audiences should be careful to monitor the impact of price changes – either dynamic or otherwise – on audience diversity.

If you’re already pricing dynamically, it’s worth pausing to consider whether you can answer the question ‘As your prices rose, who stopped buying?’ As the price rose from £40 to £50, did people who tend to book 10+ times a year drop off? At £60, what happened to the people who used to book low-price tickets once every couple of years, over a very long tenure? At £100, is the audience becoming more geographically local, pricing out people travelling from further afield? Ultimately, the more you push price, do you end up narrowing your audience base? The answer may be yes – and what might the long-term impacts of that narrowing be if, say, a pandemic comes along sometime soon?

All this said, dynamic pricing often works out well, particularly for high-demand programming, which is why it’s growing in popularity. The end result is that the house is full, and more money is taken than otherwise would have come in. If the show is good, people are happy.

We know that people are happy because we tend to ask them afterwards. The Peak-End Rule is a cognitive bias that says we judge an experience largely on how we felt at its peak, and at its end. If we complete a post-visit survey it’s often soon after we’ve left the venue or early the next day. Our responses are often heavily influenced by the Peak-End Rule – ‘I had a great time!’

How often though do we test the consumer’s emotional reaction not to a show or event, but to the actual act of ticket purchase, given how important that transaction is as a touchpoint? Rarely. And so we often don’t know:

- Whether the buyer had to dip into credit to purchase – and if they did whether we’ve reduced their future purchase intent.

- How they felt about the price/value exchange at the point of purchase.

- If, in between purchase and attendance, the purchaser felt any ‘buyer’s regret’ because they felt forced into spending more than they intended.

- Whether a higher price on a ticket affected their secondary spend intention.

As a sector, we’re behind in interrupting non-buyers as they leave our sites to understand abandoned baskets better. We’re often far more interested in the end, rather than the whole journey. This leaves a gap in our knowledge for longer-term relationship building.

Headlines and harms

Generally buyers can cope with the idea that a price may be fluid – just ask any motorist who sees the price they pay at the pump change day to day. What we really don’t like is when the price rises to something which feels uncomfortably high or unfair, perhaps way beyond where our expectations were anchored. These days many of the headlines about dynamic pricing are in fact about high prices – these may or may not have been reached dynamically.

So if you’re considering dynamic pricing, what are the things to watch out for?

In our experience, dynamic pricing tends to be open to criticism when:

A fast speed of sale is used as a powerful signal to increase prices with similar speed – so the number of tickets sold at base price ends up being relatively very small, because price uplifts take off quickly. In the UK, this risks contravening Advertising Standards Authority guidance that ‘from’ prices, particularly in print, “Must not exaggerate the availability or amount of benefits likely to be obtained by the consumer”.

The top-end of prices is stretched and the advertised highest prices end up shocking an Average Consumer*. This is most likely to generate public push-back and is particularly problematic for organisations whose work would not be possible without public funding, who need to demonstrate broad audience relevance.

The number of adjustments is so frequent the prices lack stability in any given moment.

The value exchange becomes irrational – for example where the last seat to be sold, tucked away at the back of the gallery behind a pillar, sells for more than a prime seat at the start of the sales run. Selling a seat in those circumstances arguably causes the buyer harm.

Harm? Isn’t that a bit strong?

The concept of causing a consumer harm is well established in the language of market regulators. A recent UK government consultation into drip prices – additional charges which are unbundled from a base price – defined harmful drip prices as “mandatory, pre-selected, or optional. Presented past the halfway point of the checkout process, costing more than 25% of the product price, or consisting of 3+ dripped fees”. 93% of event ticketing providers sampled contained one or more of these ‘harmful’ factors.

In 2021, again in the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority released a report on ‘Algorithms: How they can reduce competition and harm consumers’ which also warned that the potential for personalised pricing could cause consumers harm because the pricing would be opaque.

If they haven’t firmly intervened yet, we should be mindful that the authorities are watching – and not only in the UK, the same is true in the EU, and of some states in the USA, most notably in the New York State Senate.

Who should do dynamic pricing?

Since 2020, we have consulted for many visitor attractions based in globally popular capital cities. These, heavily dependent on the inbound tourist market, operate on the model of maximising income from a single visit. For any organisation whose model works in this way, dynamic pricing coupled with a range of other sophisticated ticket tactics could be the obvious go-to solution.

Likewise, entirely commercial promoters, or promoters bringing big-name shows or starry performers will tend to have more leeway to push to the outer reaches of price/value exchange and may or may not use dynamic to do so.

Other venues and attractions may want to build the practice into their terms and conditions, to adopt it opportunistically when the time is right.

Who should be more cautious?

For organisations that wish to increase audience frequency and tenure, and in particular in venues where most shows, concerts or exhibitions don’t sell out, variable pricing remains a completely valid alternative to dynamic, powerfully capable of increasing revenue.

If, as outlined above, the best way to do dynamic is to keep a cool head when deciding just how far you’re willing to push prices, then there’s a strong argument for setting the prices once, at the highest tolerable level, and then have done with it – it’s less work for you, there’s more transparency for the buyer, and overall there is less risk of consumer harm. You can also use price to drive audience behaviour because buyers ‘get’ the rules more clearly.

In particular, where cultural organisations are currently in a rebuilding phase, with audiences lost to the pandemic and cost of living, a good strategic response right now is to focus on maximising audience volume for medium and long-term recovery, i.e. keeping people in, and getting people into, the habit of cultural attendance as much as possible. So understanding who you lose when prices are increased becomes ever more important.

In these circumstances it’s not always a question of ‘dynamic pricing: yes or no?’, but ‘when and how?’ It may be wiser to first prioritise growing audience volume above all, without the distraction of ever-changing prices. Indeed – given recent headlines around dynamic pricing – those sellers who don’t adopt the practice may want to make a virtue of this in their marketing.

Ultimately, like all change, you need to be satisfied that dynamic pricing will give you both a return on investment and a return on your time. If it will, then a wise ticket-seller – with one eye on the regulatory environment – will opt for a sensible balance between speed or ease-of-use on the one hand, and pricing transparency on the other in the checkout process. Regulators and consumers are looking to us to act responsibly.

This blog post was originally published by Spektrix on 8 November 2023.

* nb. This article was updated in September 2024 to re-word the second of the four ‘tests’. The Average Consumer is a fiction / benchmark of a general, informed, and reasonably observant individual which exists in UK ‘Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations’.