Pulse report: The art of pricing

Analysis of the findings from the ground-breaking research conducted in partnership with Arts Professional which gathered the views of the sector on whether – and how – arts organisations are balancing competing objectives.

As arts organisations become increasingly reliant on earned income, there is mounting emphasis on developing sophisticated pricing strategies. These strategies have to balance the need to increase income to help pay for artistic programmes with ensuring the pricing strategy itself furthers an organisation’s vision and mission, and achieves its social objectives.

It’s a balancing act that resonates with many. A survey that ran from 3rd June to 1st July 2019, distributed by Baker Richards and among readers of Arts Professional, generated 629 complete responses, nearly all from people working in arts or cultural organisations. Of these, nearly two-thirds (64%) of respondents were working for an organisation that sells tickets or admissions, and half were involved in ticket pricing decisions.

Read the full survey responses in the The Art of Pricing summary report, including 640 – many very detailed – comments related to pricing in the sector.

A more detailed discussion of questions about affordability and concessionary discounts emerging from the survey can be found in “Is price a reason for low engagement – or just an excuse?”.

Attitudes to pricing

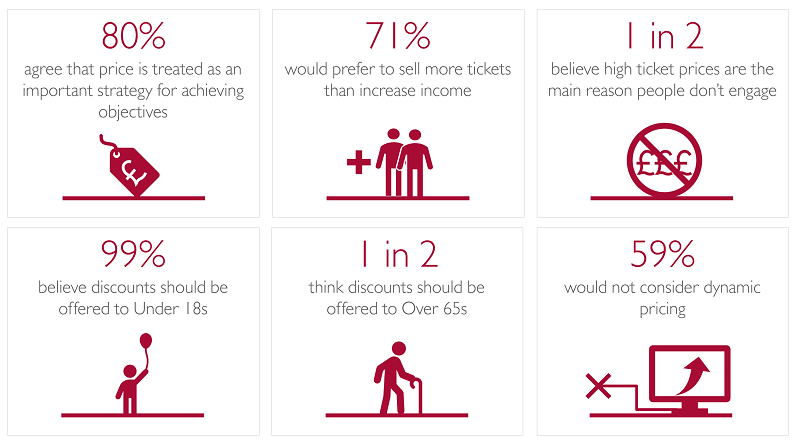

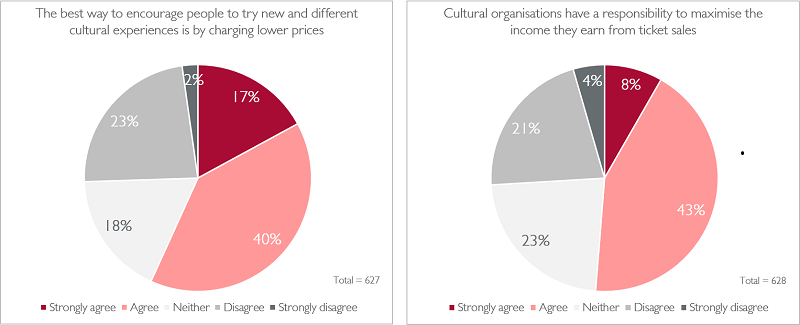

Half of survey respondents said they think high ticket prices are the main reason why more people don’t engage with the arts. And the majority of respondents believe the best way to encourage people to try new cultural experiences is by charging lower prices.

These beliefs are surprisingly out of step with evidence from our work on cultural pricing around the world. In practice, prices are only one – and rarely the most significant – reason why more people don’t engage with the arts. Low prices are seldom sufficient on their own to encourage people to try new cultural experiences.

This reality is better understood among those who are actually involved in setting prices. 46% disagree that high prices are the main barrier to attending, compared to only 31% of those not involved.

“There’s no one-size fits-all solution”

In fact many respondents’ comments demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of the much more nuanced relationship between price and demand in the sector.

“Sometimes low ticket pricing is used as the only way of overcoming barriers when other cultural barriers – how the work is talked about and described, expectations about the sheer logistics of getting to the theatre and uncertainty about the etiquette or just the nature of the experience are not addressed. Of course price is and can be an issue, but it’s not the only one”. (40)*

The comments reflect many different perspectives, partly arising from different scale, art form, business model and market-related factors – rural vs urban vs London – as well as across subsidised vs commercial activity.

Just as striking are the different perspectives offered according to respondents’ roles in the sector. There were many responses from managers, who recognise the importance of pricing and clearly think hard about the implications of their decisions. But there were also comments from more junior arts workers who can’t afford to attend (as often as they’d like), and some artists, with a particular perspective on how the public values (or doesn’t) what they do and how that affects their ability to earn a living.

“The expectation of artists and what they get paid is reasonable but the expectation of the audience to pay appropriately for the performance they receive is not in line with the costs”. (74)

It’s not about price, it’s about value

The comments also reveal a widespread understanding that the key issue is not what price is being charged, but the perceived value of the arts experience to potential audiences.

“Price is a red herring. It’s value that theatre lacks in the minds of audiences”. (44)

“I think pricing is a convenient excuse that is often ‘trotted out’ to provide an easy answer”. (158)

Several comments observe that potential audiences, including so called ‘hard to reach’ audiences such as young people, will pay substantial prices for stuff they value: football, festivals, etc. Price is not usually the reason working class young men choose to go to football matches rather than dance performances.

It is worth noting that, despite frequent press commentary about the apparent ‘problem’ of high prices in the West End, commercial producers can only charge high prices because people will pay them.

“Young people will pay hundreds of pounds to go to Glastonbury but not £10 to attend their local theatre to see a play that might be staged at Glastonbury”.(182)

“Usually it’s not the ticket price that is the problem – it’s convincing people that they will enjoy the work in the first place”. (103)

Accessibility is about a whole raft of complex things, only one of which is price. A better emphasis would be on affordability and exploring the challenges in delivering truly affordable arts experiences, including implications for concessionary pricing.

Some comments reflect what may be an important related trend: audiences will pay high prices for a ‘special event’ or (occasional) ‘big night out’ but are more price sensitive for ‘run of the mill’ performances. Research by numerous agencies has shown consistently over the years that most people attend the arts very infrequently (once a year or less), so it appears that price is mainly a problem for the regular visitors who typically make up a higher proportion of the audience for those ‘run of the mill’ performances.

Some respondents expressed concern that the market is becoming more focused on ‘special event’ entertainment and that those high prices are cannibalizing available spend. They share their frustrations that blockbuster exhibitions at the major galleries are overwhelming smaller scale exhibitions.

“The visual arts find it difficult to charge and most audiences won’t pay for exhibitions outside of blockbuster ones in London. This means the visual arts find it difficult to generate income other than from grant funding”. (169)

Several comments also point out the importance of understanding how public perceptions of value are formed and how higher prices can signal higher value. Promoters of ‘special events’ are in a good position to take advantage of this.

The corollary is that low prices can undermine perceptions of value. Focusing on price, rather than communicating extraordinary value offered by a cultural experience, is counterproductive if the potential audience neither values culture highly nor appreciates the costs of promoting events. Indeed, they may even confirm the public’s view that their disposable income – and that even scarcer resource, time – be better spent elsewhere.

“I feel strongly that if more energy was invested into engaging audiences in cultural activity, higher prices would not be the barrier we imagine it to be. Arts and culture should be valued more highly, not made cheap”. (82)

Objectives and practice

Respondents on the whole agree that their organisations treat price as an important strategy for achieving objectives. Comments generally suggest that having a range of prices is fundamental to an effective and affordable pricing strategy and the key challenge is how to apply price discrimination fairly in relation to affordability. There is also an appreciation of the importance of making good quality inventory available for audience development initiatives.

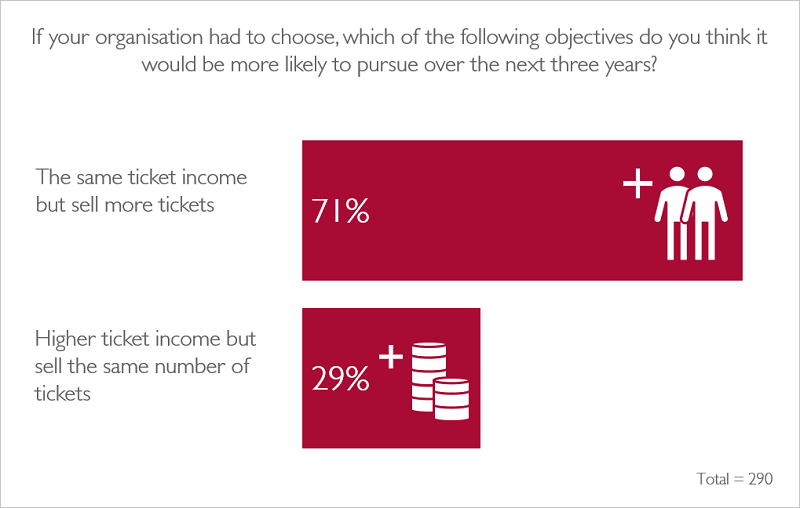

So at a time when the outlook for public funding appears particularly uncertain, it is interesting to note the overwhelming majority would rather sell more tickets than achieve an increase in income. It appears that cash-strapped or not, arts organisations resist pricing strategies that could increase their revenues, for fear of losing audiences.

It’s possible that those who focus on selling more tickets do so because of excess capacity, while those who focus on generating higher income may not have many spare seats available. If so, this would simply highlight one of the key aspects of pricing in the sector: that the perishability of inventory (the fact that you can’t sell an empty seat after curtain up) has a significant impact on how we think about demand and pricing. Any income for an unsold seat five minutes before a performance is income that would otherwise be lost forever. In most cases, the incremental cost of selling another ticket is close to zero, so there is no real reason not to take what you can.

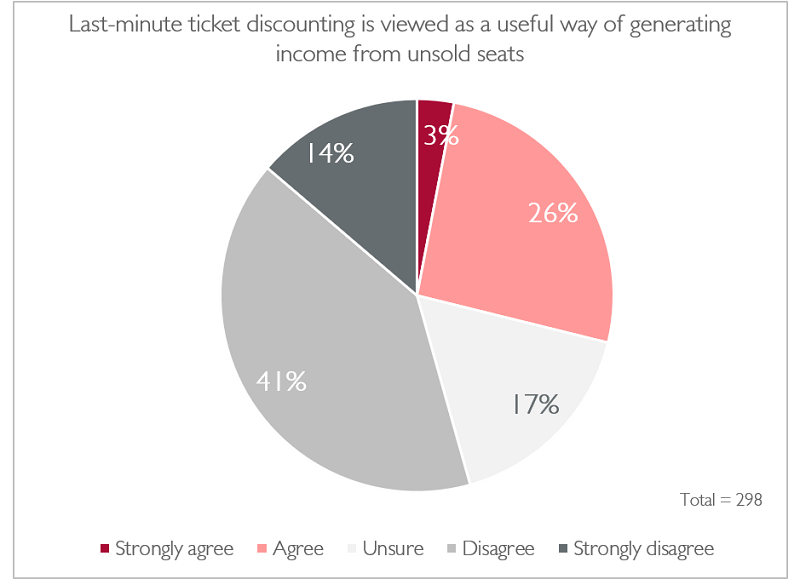

Yet more than half of respondents said their organisations do not view last minute discounting as a useful way to generate income, reflecting at best an ambivalence about promotional discounting.

Comments suggest most respondents understand the danger of last-minute discounting undermining perceptions of value, as well as usually being quite ineffective.

Is there a role for dynamic pricing?

What seems to be less well understood is that revenue management tactics – as frequently employed by airlines – are actually about addressing the problem of filling unsold capacity, just as much as maximizing income from tickets in high-demand and short supply. But there remains considerable scepticism about their use in the sector. Almost half of all respondents believe the use of ‘airline pricing tactics’ is inappropriate, while only a third think it is appropriate.

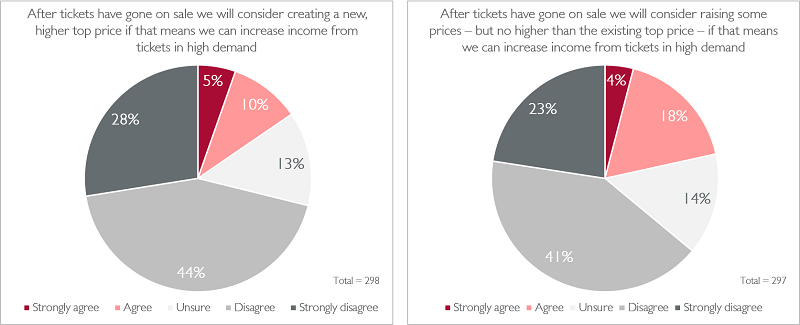

Among those actually involved in price setting, over 60% won’t consider raising any prices at all after tickets have gone on sale and over 70% would not consider creating a new higher top price, even if that means they could increase income from tickets in high demand.

This reluctance suggests that the sector is missing a huge opportunity to maximise income – something that is at odds with the widespread recognition that organisations do have a responsibility to maximise revenue.

“Dynamic pricing is widely misunderstood, as its primary goal is to maximise attendance, rather than necessarily maximise income from ticket sales”. (265)

“Dynamic pricing can be used in a ‘Robin Hood’ way to ensure that those who can and will pay more subsidise offers to appeal to new and less engaged audiences”. (141)

Many of our clients have been able to significantly increase income by using dynamic pricing to unlock the value of tickets which were difficult to price accurately when they went on sale. This flexible approach to pricing recognises that the right price is what someone will pay for it.

There are, of course, circumstances where dynamic pricing is not appropriate, such as when substantial volumes of tickets are purchased early by regular attenders, who also make substantial donations. And dynamic pricing does reinforce inequity for those on low incomes – a fact that generated a range of comments and insights. As with ‘affordable’ pricing, the danger is that those in the know are always best able to work around any strategy to their advantage.

The other big challenge for dynamic pricing, is that in order to respond to market demand, sometimes prices need to go down as well as up and simply reducing prices can undermine perceptions of value, particularly amongst those early core audiences who paid full price.

Business models and pricing

The survey generated responses from presenters, producers and venues that do both. Several comments reflect the different perspectives of these two groups. Venue managers refer to greedy producers who set prices too high, while producers complain about how venues are constantly chiselling away at deals through inside commissions, ‘restoration funds’ and the like. As more organisations move transaction fees ‘inside’ the published price, fees become just part of the deal and invisible to customers. So maybe now is the time for this constant competition for a larger slice of the pie to be set aside in favour of longer-term, more collaborative customer-focused approach across the whole sector supply chain.

In this context, the potential value of other sources of income from customers is receiving increased focus, including ancillary income (food and beverage, retail, etc.) and affiliation (low level donations and memberships).

Just over half of all organisations had a membership scheme. Of those, 73% offered free or discounted tickets for members. It’s the standard approach in the visual arts, and can make a lot of sense for venues, especially where they are mainly presenting rather than producing work. However, there is a big danger of sending out mixed messages if what your scheme is trying to generate is philanthropic giving while your key benefit just gives money back and if you are not careful, can result in a membership that actually costs money.

23% of organisations operating a membership scheme provide booking fee exemptions or discounts for members. This can be motivating to customers but will cease to be an effective incentive if transaction fees are moved ‘inside’ the ticket price. Nearly half (44%) of those with memberships offer free or discounted merchandise, food, drinks, etc. and this is a cause for concern because those areas of ancillary income tend to have very tight margins and can quickly become un-profitable… which begs the question about the purpose of such operations. (For more on this read The AAA of income).

In a wider context, several comments point out the challenge presented by Netflix and the like, which have changed expectations about how a ‘subscription’ model should work. But also, the increased popularity of this ‘stay at home’ entertainment may have shifted expectations around the cost of an evening’s entertainment. Might this also relate to the trend noted above about an increased focus on ‘special occasions’ and events? These are challenges that will require solutions going far beyond pricing strategy.

Conclusion

While this survey has generated many thoughtful comments illustrating a nuanced understanding of the complexity of pricing decisions, it suggests there is more work to be done to help organisations achieve their commercial potential. Continued resistance to dynamic pricing as an income opportunity; challenging a focus on pricing ‘schemes’ at the expense of creating and communicating value and relevance; and developing a more nuanced understanding of the issues around accessibility, affordability and what pricing can (and can’t) do are three subjects that warrant much more attention.

For the wider ecosystem, there are misconceptions about the relationship between price and attendance; questions around managing relationships between producers and presenters and the balance of programming; and more philosophical issues around the relationship between funding and pricing in the subsidised sector. We look forward to continuing working with organisations to address the issues and opportunities to create a thriving cultural sector.